Our newly adopted stray Mella was obviously not a member of the feral cat colony which occupied our neighborhood. The feral cats would do anything to avoid humans as much as possible, even if that meant using storm drains as a travel system and only venturing out for food late at night. But Mella purposefully sought human contact— shortly after we found her we learned that most of our neighbors already knew her and had fed her dinner on several occasions. But even though she loved to be near people, she was still more like a bobcat than she was a house cat. She had spent her life climbing trees and hunting, not lounging in windowsills and eating hand delivered food.

For Mella’s own safety (and for the safety of the small wildlife she hunted) we helped her transition from wildcat to indoor cat. She eventually grew to love life indoors, but she did not appreciate the change at first. She spent her days plotting an escape back to the outside world instead of enjoying her new worry-free lifestyle. We worried that her attempts would be successful, so we quickly scheduled her spay surgery to prevent her from having kittens without homes.

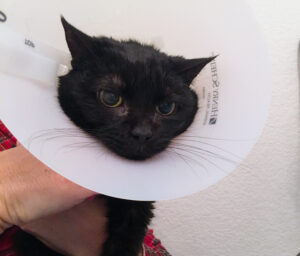

We already thought Mella was angry enough indoors, but her strict postoperative recovery instructions made her even more enraged than we anticipated. Not only was she required to rest and forbidden to jump on the roof to chase squirrels, but to make matters even worse she also had to wear an embarrassing e-collar (otherwise known as the “cone of shame”) for two weeks.

“It looks like her incision is almost healed, I wish we could just take that thing off,” Mom said sadly one day as she watched Mella try to wiggle out of her e-collar for the hundredth time. But despite Mella’s death glares and pitiful meows, we resisted the temptation to remove her e-collar until she completely recovered.

Forcing Mella to wear the e-collar caused a temporary rift in our relationship, but neglecting the e-collar and allowing her to lick or pull her sutures would have jeopardized her recovery. If she damaged her sutures, she could’ve opened the incision, increased the possibility of infection, prolonged her recovery, and risked the need for another surgery— all potentially life-threatening. No matter how furious she became, her frustration with her e-collar was not worth her life. In comparison to serious health risks, the relatively minor annoyance of her e-collar was undoubtedly in her best interest.

E-collars are absolutely necessary for surgical patients. If the patient is able to lick or pull their sutures, they greatly increase their risk of postoperative complications which are typically preventable with e-collar use. The e-collar also must be worn for the entire period of time the veterinarian prescribes. An incision may appear healed on the surface, but might not have actually healed completely. Because it is not possible to closely supervise the patient at all times, the e-collar most effectively reduces the probability of preventable postoperative risks.