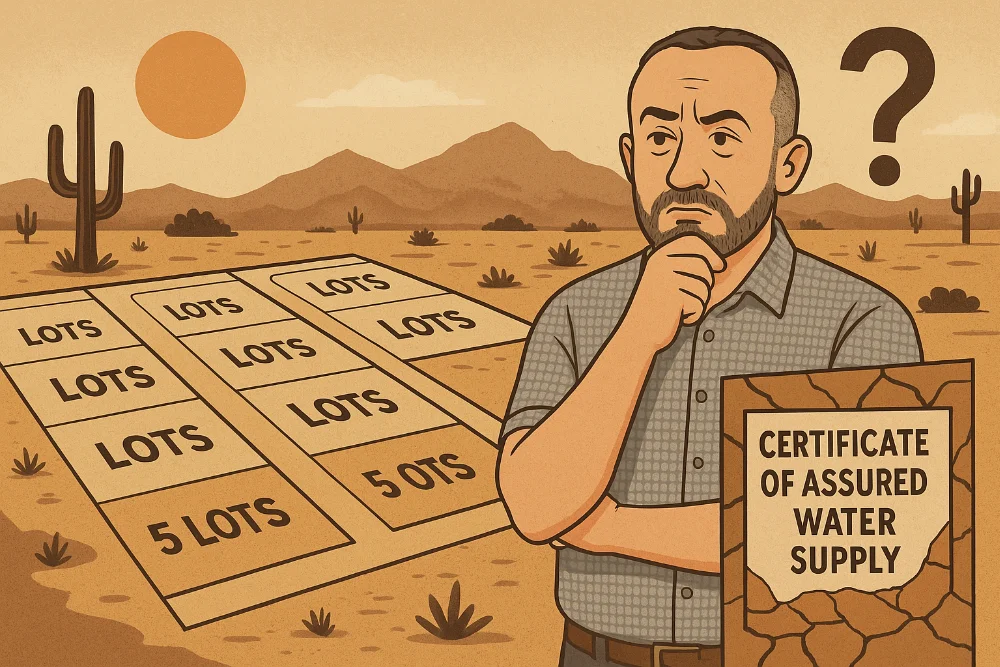

In Arizona, growth and water security are deeply intertwined. The Certificate of Assured Water Supply (CAWS) is a key regulatory tool under the state’s 1980 Groundwater Management Act, requiring that any new subdivision with six or more lots demonstrate a 100-year water supply before it can be legally recorded.

It’s a rule designed to protect both homeowners and the environment—ensuring that new communities won’t run dry. But with the current moratorium on groundwater-based CAWS in the Phoenix Active Management Area, many developers have found themselves in a bind. Without alternative water sources, subdivision plats can’t move forward.

That’s where a loophole has been getting more attention.

The Five-Lot Workaround

Under Arizona law, a land division of five or fewer lots does not require a CAWS. This exemption was originally intended for small, low-impact developments—think family land splits or boutique rural projects.

Now, some developers are subdividing land in increments of five lots or fewer to avoid triggering the CAWS requirement altogether. In some cases, these smaller splits are later recombined through creative ownership transfers or further phased divisions—effectively building a larger project without going through the formal water certification process.

Why This Is Happening Now

- CAWS Moratorium – Since June 2023, the Arizona Department of Water Resources has stopped issuing new groundwater-based CAWS in the Phoenix AMA due to projected shortages over the next century.

- Development Pressure – Arizona remains one of the fastest-growing states in the U.S., and housing demand—particularly in Buckeye, Queen Creek, and other outer-metro areas—remains high.

- Alternative Supplies Are Limited – Securing non-groundwater sources, such as CAP surface water, reclaimed water, or water importation, often requires years of planning and significant infrastructure investment.

The Risks of Avoiding CAWS

While the five-lot strategy can move a project forward in the short term, it comes with significant drawbacks:

- No Guarantee of Long-Term Water Supply – Without CAWS review, there’s no formal verification that water will be available for a century.

- Infrastructure Inefficiencies – Designing utilities, roads, and drainage for piecemeal developments can lead to costlier, less cohesive systems.

- Legal and Policy Scrutiny – State lawmakers have signaled interest in tightening subdivision rules to prevent “CAWS avoidance” through serial lot splits.

- Market Risk – Homebuyers are becoming more aware of water security issues and may be cautious about purchasing in uncertified developments.

Civil Engineering Implications

From an engineering perspective, bypassing CAWS can complicate:

- Utility Planning – Designing infrastructure for incremental expansions rather than an integrated subdivision layout.

- Stormwater & Drainage – Coordinating site-wide systems when development occurs in disconnected phases.

- Roadway Connectivity – Ensuring traffic flow and emergency access meet standards without unified subdivision review.

- Regulatory Compliance – Navigating county, city, and state oversight without triggering unintended violations.

The Path Forward

Instead of working around CAWS, many experts argue for:

- Regional Water Partnerships – Collaborating with neighboring jurisdictions and private utilities to share alternative water infrastructure.

- Investment in Reclaimed Water – Building treatment facilities and purple-pipe distribution systems to offset potable demand.

- Legislative Reform – Updating the subdivision definition to prevent serial lot-splitting while providing workable paths for smaller developers to certify water.

- Long-Range Water Banking – Securing and storing water now for future use, especially in growth corridors.

Conclusion

The five-lot exemption was never meant to be a growth engine—but in today’s regulatory climate, it’s become a workaround for developers facing Arizona’s strict water rules. For civil engineers, this creates unique challenges in planning cohesive, sustainable infrastructure under fragmented approval processes.

Ultimately, whether through policy reform or alternative water investment, Arizona’s long-term growth will depend on aligning development practices with secure, verifiable water supplies—no matter how many lots are in the subdivision.